The explanation of human behavior is complicated. Why do we do the things we do? What pushes us to act on our instincts?

Theorists have been researching human behavior since the beginning of time, looking for explanations behind various aspects of social phenomena that are supported by empirical evidence. Many theorists have offered possible reasons behind why people act as they do using a specific concept or idea. Together, these theories help provide us with an understanding of the workings of human behavior.

One human behavior that has a number of theories behind it is motivation. And while each theory is rather specific, if you look at the principal ideas behind each one, it can help you gain a more comprehensive understanding of motivation.

According to the Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology, motivation is the force that initiates, manages, and maintains our goal-oriented behaviors. Motivation is what compels us to take some sort of action, which can be as simple as reaching for a snack to satisfy a craving or as significant as moving across the country. When we are moved into action, it’s either by the push of a motive or the draw of an incentive toward some end-goal.

Understanding what makes you do the things you do can be helpful in a quest to live a more fulfilling life and establish effective decision-making processes. When you can better understand the forces that drive your actions–which can be influenced by your physiology, emotions, cognition, or social factors–you can also understand how to change your path if you can’t seem to get motivated to do the things that you know are important.

No individual motivation theory explains every aspect of human behavior, but the theoretical explanations that we will look at in this article can help you develop new approaches to increase your motivation in domains in your life where it may be lacking. Let’s take a look.

7 Top Motivation Theories in Psychology Explained

1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a tiered model that is depicted using a pyramid to show the basic human needs that have to be fulfilled before one can live up to their true potential.

According to this pyramid, our most basic needs are those of survival, and these are the primary things that motivate behavior. This makes sense, as you’re not going to live each day chasing after a feeling of prestige if you have no access to food or water. Your biological requirements for survival need to be met before you’re motivated to address other factors in life, and the motivation to fulfill these needs become stronger with time (i.e. the longer you go without sleep, the more tired you will be). Once this level is fulfilled, the next level in the pyramid becomes the source of your motivation, until you reach your full potential.

The first four needs in the pyramid are “deficit” needs, meaning that you’re motivated to satisfy a void in these areas. Let’s take a look at each of these needs:

Physiological needs

These are biological requirements for survival, such as air, food, water, sleep, and shelter. Your body can’t function if these needs go unmet, and all of your other needs are secondary until these are fulfilled.

Safety needs

Once your physiological needs are satisfied, the need for safety and security become pertinent. People yearn for stability, predictability, and a sense of control. This includes emotional security, financial security (having a job), stable health, and safety from danger, accidents, and injuries.

Love and belonging needs

The third level of human needs involves a need for interpersonal relationships and being a part of a group. This includes having friends, experiencing intimacy, loving and trusting others, being accepted, and feeling loved.

Esteem needs

Maslow classified esteem needs into two categories: self-esteem and the inclination to feel respected by others. Maslow further explained that the need to have other people’s respect is felt the most early on in life and takes precedence over a sincere feeling of self-esteem.

Maslow posits that people do not need to completely fulfill one need before moving onto the next. He explains that a “deficit need” simply needs to be “more or less” satisfied before one’s actions become more directed toward fulfilling the next stage of needs (i.e. you may not have gotten your full 8 hours of sleep before your focus is shifted more towards your physical safety).

The top and final level in the pyramid defines your “growth” needs, which aren’t caused by lacking something, rather they stem from an aspiration to grow as a person. While all people are capable of reaching the highest level of self-actualization, many people never get there. Progress is often obstructed when lower level needs aren’t met due to a variety of circumstances in life such as:

These experiences can cause people to move back and forth between the levels of the pyramid, depending upon their needs at the time.

The process of becoming self-actualized varies from person to person, and it isn’t about living a “perfect” life. People can focus on this need in very individual and specific ways. While one person may want to be a model parent, another may want to achieve athletic excellence. Realizing one’s full potential–regardless of what that means to you– includes achieving sensible psychological health and a secure sense of fulfillment. People who achieve self-actualization:

When it comes to human motivation, Maslow concluded that the actions we take are usually derived from more than one motivation. For example, you may be motivated to get a project completed at work on a strict deadline to fulfill a need to gain respect from your co-workers (esteem needs), to maintain feelings of acceptance from others at your company (belongingness needs), so you have a sense of job security (safety needs), in order to feed yourself and your family (physiological needs).

All in all, this theory argues that people act to satisfy their deprived needs.

2. Alderfer’s ERG Theory

The focus of improving employees’ job performance has been at the epicenter of many theories of motivation–including Clayton Alderfer’s. This is likely because so many people can relate to either being an employee or an employer, and these systems are what keep people’s everyday needs met. You need people working at your local grocery store so you can buy groceries, you need people to drive large tanker trucks to deliver gas to your local gas station, and you need doctors who can examine you when you’re sick.

Clayton Alderfer refined Maslow's hierarchy of needs by categorizing Maslow’s pyramid into a theory of Existence, Relatedness, and Growth, with a primary focus on esteem and job performance. Let’s take a look at these needs individually.

Existence Needs

These include both material and physiological desires–which is everything in Maslow’s first two levels of needs.

Relatedness Needs

This addresses social and relationship needs. It’s about your desire to:

When compared with Maslow’s hierarchy, relatedness needs are the same as the third and fourth levels of the pyramid.

Growth Needs

Your growth needs are what drive you to be productive and live a meaningful life. In Alderfer’s theory, this is equal to Maslow’s self-actualization.

But, unlike in Maslow’s hierarchy, Alderfer didn’t posit that a lower level need must be fulfilled before one can move on. This allows the order of these needs to vary in importance from person to person.

Alderfer also theorized that once a person’s lower needs are met, they become less important; however, the more people pursue higher needs, the more important they become (i.e. once you have solid relationships at work, that need is met and put on the backburner, but the higher you move up the corporate ladder, the more important it will be to you to continue to achieve success at work). This greatly differs from Maslow’s theory because according to his hierarchy, you will always need air to breathe in order to meet a greater need–the levels never lose importance.

While the priority of Alderfer’s needs may be different from one person to the next, he addresses each categories' concreteness, with existence needs being the most concrete, and therefore the easiest to confirm. Relatedness needs, which depend on your relationships, are less concrete, and growth needs are the least concrete because their objectives vary upon the uniqueness of each individual.

Alderfer also introduced the “frustration-regression” process, which is a phenomenon he observed that explains when people are unable to meet their higher needs, they may regress their attention back to lower needs.

This is key in workplace environments, as when a sense of autonomy is prevented, employees may regress their focus to a sense of security or belongingness their job gives them. This is a key point for employers to know because it suggests that if employees aren’t given growth opportunities, they’re likely to alter their focus to meeting their social needs by spending work hours socializing with colleagues, therefore wasting company money on payroll.

According to employment coaches, this theory has further implications in a work environment, as managers need to recognize their employees' multiple co-occurring needs. In Alderfer's model, focusing on only one need at a time won’t motivate employees. If, as an employer, you can recognize early on that your employees’ needs aren’t being comprehensively met, you can take appropriate steps to address any frustrated needs in order to maintain your employees’ motivation.

Furthermore, while financial incentives can satisfy employees’ growth and recognition needs, they can only do so indirectly, depending upon their perceived value by the individual. So employers can offer financial incentives, but if employees’ other needs aren't met, they won’t be motivated to do their best work, according to Alderfer's theory.

3. McClelland's “Acquired Needs” Human Motivation Theory

David McClelland took a different approach to thinking about needs and argued that one’s needs are developed over time and learned through experiences, and therefore didn’t focus his research on the idea of satisfaction.

McClelland theorized that humans are motivated by three needs: achievement, affiliation, and power. He proposed that people’s behavior and sense of motivation is influenced by these factors, with one of them always being dominant over the others. Everyone’s dominating driver is shaped by their unique life’s events.

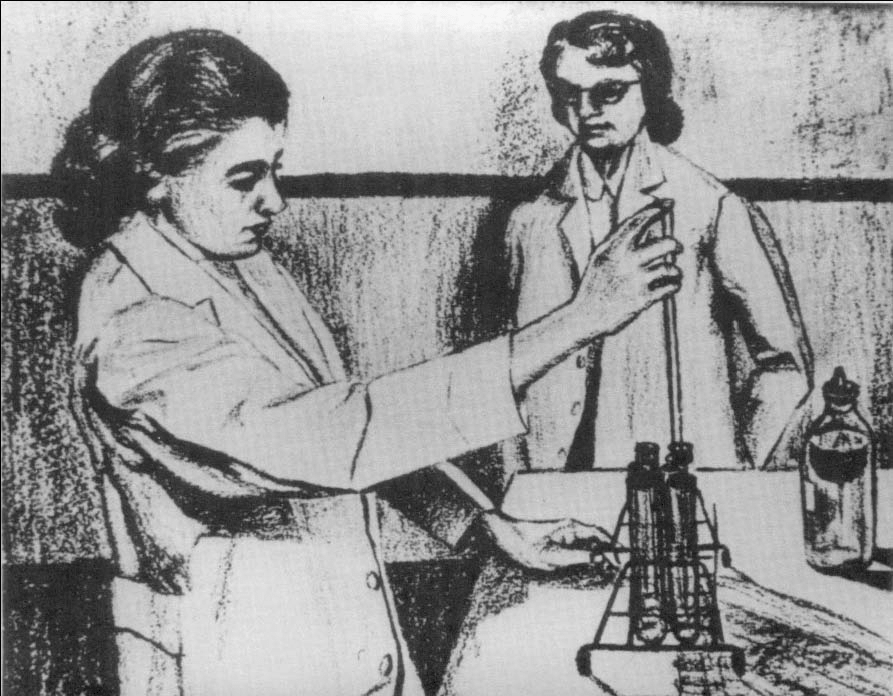

McClelland used a Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) to assess people’s dominant needs. This method involves showing research subjects a vague picture, such as this one:

and then having them come up with a story based on the picture. Who are the people? What are they doing? Why are they doing it? The story that a subject told was then analyzed by experts and would reveal how their mind works and what their sources of motivation are.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these drivers of motivation.

Achievement

Those who are motivated by achievement are driven by opportunities to show other people their competence. Because of this, they enjoy working on individual projects so they can earn all of the credit for success. They avoid low- and high-risk situations, as low-risk tasks don’t display any genuine achievement and high-risk tasks involve a component of chance to attain success. These people are also motivated by the prospect of receiving immediate recognition for their efforts and progress.

This population is always aiming to improve upon their past performance. They are goal-oriented and often enjoy working toward stretch goals that are incrementally challenging. This is a great source of motivation for people who work in sales, as there are explicit goals to meet and they’re able to receive immediate feedback for their efforts.

Implication for employers: Managers should give their achievement-driven employees challenging projects with attainable goals. They should also give these employees frequent positive feedback.

Pitfalls: When working in lower level positions, employees who are motivated by achievement are often promoted due to their performance. But, once in a management position, having a high need for achievement comes with significant disadvantages, as managing other people requires spending time training, coaching, and meeting with employees to get work accomplished rather than doing it yourself.

Furthermore, because people with a high need for achievement prefer doing the actual work, they struggle with delegating tasks to others. They tend to micromanage and want people to work in very particular ways, and therefore may become overbearing bosses due to their high expectations.

Affiliation

People motivated by affiliation thrive off feeling a sense of belonging and acceptance by their peers. They comply with social norms and frequently socialize with others. Because they enjoy personal interaction, they tend to avoid interpersonal conflict at all costs.

Implication for employers: These employees perform best in a teamwork environment.

Pitfalls: Having a need for affiliation can again be a disadvantage for those in management positions because these people are typically overly concerned about how other people perceive them. They might have a hard time offering negative feedback or disciplining employees who aren’t performing well. Because of this, they may create a work environment that accepts mediocrity, which could cause some of their high performers to leave the team.

Power

McClelland further divided power into two categories: personal power and institutional power. People motivated by personal power feel a need to be in control of other people. They prefer to be in authoritative positions that are associated with status and are less concerned with their work performance than with their level of control over other people.

Alternatively, those with a need for institutional power want to influence other employees to meet the needs of their corporation. People who desire institutional power are often more competent managers than those with a need for personal power.

Implication for employers: Management should offer these employees leadership opportunities.

Pitfalls: Being motivated by power is an important trait for effective managers to have. However, this need can be a destructive factor in professional relationships if it takes the form of using power to only benefit oneself.

It’s important for managers to understand the dominant needs of their employees in order to effectively motivate them. While employees with a high need for achievement will likely respond to having concrete goals, those with a need for power may try to influence other employees–which could be positive or negative for the company. Finally, employees with a need for affiliation will be motivated by the prospect of gaining the approval of their colleagues.

In order to increase the effectiveness of employees, employees should be made aware of the common pitfalls associated with their source of motivation.

4. Vroom’s Theory of Expectancy

Victor Vroom posited that people decide upon their actions based on the outcomes they expect. In a professional environment, this might mean that someone works longer hours because they expect a pay raise.

He theorized that people are highly productive and motivated if two conditions are met:

1) People believe they will succeed in their efforts.

2) People believe they will be rewarded upon their success.

People are motivated to work hard when they believe there’s a correlation between their efforts, their achievements, and the rewards they obtain. This theory assumes that people’s behavior is the result of conscious choices they make in order to maximize pleasure and to minimize pain.

Vroom uses three variables in his theory: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence.

Expectancy

Expectancy encompasses the thought process of “If I work harder, I’ll perform better”.

This is impacted by:

- Possessing appropriated resources (such as materials, information, and time)

- Having the required skills to get the job done

- Being supported in your endeavors (having your supervisor’s support)

Instrumentality

Instrumentality is the thought process of “If I perform well, I’ll be rewarded appropriately”.

This is impacted by:

- Having a clear understanding of how performance relates to rewards

- Trust in others to make the right decisions regarding who receives what rewards (trusting your boss to pay people on a scale that correlates with their skills, level of responsibility, knowledge, and prestige)

- Transparency in the process of receiving outcomes

Valence

Valence is one’s perception of the value of the reward. For the valence to be motivating, the person must want to obtain the reward more than not obtaining it (so if someone is motivated by money, they may not be motivated by the prospect of earning additional time off work).

Vroom's expectancy theory highly depends upon one’s perceptions, so even if a motivation tactic works with the majority of employees, that doesn't mean it will work for everyone.

In summary, people are motivated if they believe they will earn a desired outcome if they achieve their goal. Alternatively, they’re least motivated if they don’t perceive the reward as being valuable or they don’t think doing the work will actually result in receiving the reward. So, if managers want to keep their employees motivated, they need to set achievable goals for them and provide rewards that they actually want.

5. The Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne Effect was first explained in 1950, when researchers noticed that people have a tendency to work harder (and therefore perform better) when they’re being observed by others. The original series of studies focused on altering the lighting at Hawthorne Works in Chicago and assessing the resulting impact on people’s work. The perceived increase in attention that was focused on the employees as a result of the additional lighting led to temporary improvements in production, rather than changes in working practices.

This suggested that observation can be a motivating intervention for people for all kinds of behaviors such as eating habits, exercise, work practices, and hygiene routines because these life domains have a lot of opportunity for instant modification.

The Hawthorne Effect marked a big change in how people thought about work and productivity. In order to see how people’s performance could be improved, these studies and the resulting theory set people in a social context, showing that employees’ performance is impacted by their environment and by the people around them as much as it’s impacted by their innate abilities.

This theory has been tested in subsequent studies, such as this 2006 study that observed the hand-washing practices of medical staff. The study found that when staff knew they were being watched, they complied with hand-washing standards 55% more than when they weren’t being watched.

The Hawthorne Effect has changed the way many managers think about their employees’ motivation, job productivity, and job satisfaction. The results of the studies demonstrated that improved employee performance is impacted by a complex set of attitudes. Aside from feeling the potential scrutinization of someone overlooking one’s work, the special attention put on these employees made them feel a sense of pride that also motivated them to work harder because they felt like they’re being singled out (in a good way). Managers who gave employees some autonomy or made them feel genuinely valued further increased the workers’ motivation.

Finally, this series of studies suggested that when employees work in groups, they feel a sense of pressure from the group to perform well, which has a positive impact on their motivation to succeed. The results of the Hawthorne Effect improved researchers’ understanding of what motivates people. This research added to other theories because it added in a factor of socialization needs when it comes to influencing people’s motivations and behaviors.

6. Skinner’s Operant Conditioning Theory

Unlike other theories, B.H. Skinner’s Operant Conditioning Theory doesn’t assess one’s personality, rather it is based on the idea that people behave according to the type of reward they believe they will earn as a result of doing the work. He theorized that the best way to understand motivation and behavior is to assess what causes an action and what the resulting consequences of that action are.

This theory addresses three types of responses to behaviors:

The idea of operant conditioning is relatively well-known, but do you know the ways in which you already practice this in your everyday life?

Most likely, you use its principles whenever you’re trying to create, change, or break a habit. You also probably use it when trying to come up with motivating factors for your children to act (or not act) a certain way.

In a working environment, this theory results in the formation of incentive systems. If managers want to reinforce a behavior in their organization, they offer rewards; if they want to reduce a particular behavior, they punish employees in some way.

But let’s look more at how you may use operant conditioning in your everyday life. Think about a situation that involves a stimulus (antecedent), which leads to a behavior, which then has a consequence.

An example we often refer to on this site is the act of leaving your running clothes and shoes by your bed at night. Doing this can help trigger you to go for a run first thing in the morning, as soon as you see your running clothes (which is the reinforcement). Because reinforcers are situation-specific, if you leave your running shoes and clothes in the closet, they will not have the same impact on you, which could result in skipping your run. However, if you do go on your run, you will be rewarded by feeling good about yourself due to starting your day with a healthy attitude. Seeing your work clothes laid out first thing in the morning wouldn’t have the same impact on you as seeing your running gear.

Or, let’s say you want your child to sit quietly while you’re on an important phone call and your child complies. When you get off the phone, you’re probably inclined to recognize your child’s good behavior in some way, depending on what you know your child really enjoys. This may involve offering to spend some time playing a game together or giving your child a piece of candy. This is another example of positive reinforcement.

But let’s say your child is misbehaving, so you take away their television-watching privileges for the rest of the week. Your child will then be less likely to misbehave in the future if they remember this consequence of their unwanted behavior.

You may also give your dog a treat if you’re trying to train him or get him to take a specific action (e.g. I give my dog a treat once she comes back inside after being let out for the last time before bed). Or maybe you’re training your dog to sit, so when he listens to that command, you offer a treat. Over time, your dog will associate the treat with the desired behavior.

Think about the ways you reward yourself when you reach your goals–or even when you complete a small win. Perhaps for every ten minutes you work out every day, you allow yourself to watch ten minutes of your favorite tv show that night.

Time is an important component in this theory, as very little time should pass between offering a reward (or consequence) following a behavior being exhibited so the association between the two factors can be strengthened.

This motivation theory is effective in a wide variety of situations, which is likely why it is so well-known.

7. Locke’s Goal-Setting Theory

Edwin Locke’s goal-setting theory refers to the impacts of setting goals on one’s future performance. Locke posits that goals are a key driver of one’s behavior. This goal-setting motivation theory places importance on the specificity of one’s goals, how difficult they are to attain, and one’s acceptance of their goals. The theory then provides parameters for how to integrate goals into incentive programs in order to increase motivation.

In his research, Locke found that people who set challenging and specific goals obtained better outcomes than people who set easy, general goals. Locke offered five critical principles of goal-setting: clarity, challenge, commitment, feedback, and task complexity.

Locke’s framework for setting effective goals includes:

One of the most effective ways to maintain motivation is to set high-quality goals for yourself.

Let’s say you want to lose 50 pounds. You could say:

According to this motivation theory, the simple act of setting a strategic goal improves your chances of reaching that goal.

Final Thoughts on Motivation Theories

Which of these theories can you connect to your own experiences? Which of them do you find useful?

Hopefully after reading this article, you have a deeper understanding of motivation and you are better prepared with tools that you can use to motivate yourself when it’s time to make a change.

Remember, you don’t have to stick to just one theory. You can take bits and pieces of lessons from each and apply them to your life to help you feel the necessary motivation to be successful in your endeavors.

Connie Stemmle is a professional editor, freelance writer and ghostwriter. She holds a BS in Marketing and a Master’s Degree in Social Work. When she is not writing, Connie is either spending time with her 4-year-old daughter, running, or making efforts in her community to promote social justice.